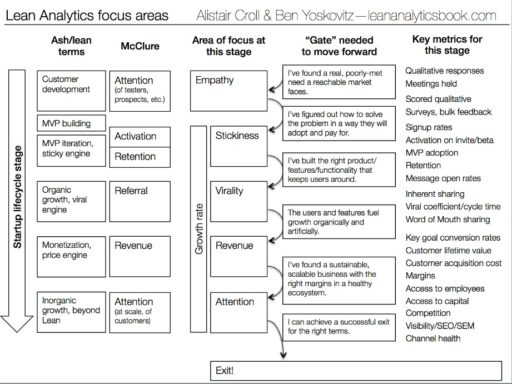

Croll and Yoskovitz do a nifty job explaining where to start- gathering relevant information, using the right metrics to act upon, and finding the OMTM so you know if your pivots are working. Their “flipbook” spotlights six business models representing six different kinds of businesses. For each, their key metrics, user flows with key metrics at each stage, case studies, examples of relevant tables with calculations, even indications of fraud and how emails may be being blocked- and so much more. Very cool stuff.

For what could easily be a bone-dry book given the subject matter, Lean Analytics is super approachable and engaging. It’s not all quantitative, data scientist stuff (not what I expected, but a little relieved nonetheless). True to other Lean Startup works, it’s written for the entrepreneur, with no presumptions about the audience having experience with the subject matter. The book is packed with case studies, examples, and visuals that make understanding concepts and calculations a snap. The amount of information and considerations presented in this book is astounding. It’s enlightening to see what can be measured with a little ingenuity. Nearly anything can be given a value- start keeping score.