Approximate read time: 8 minutes

The Top 5 Lessons I Learned as a Marketer for a Civil Engineering Firm

I once asked three engineers in my office the same questions:

If you could choose to design one thing what would it be?

As the first marketer for a civil engineering firm I wanted to know how civil engineers think and what motivates them. They took to me quickly but had no qualms about telling me that they “understood” (their air quotes) the idea of marketing and that it had its place, but they didn’t care about it and frankly, found it uninteresting. No surprise, engineers are known to loathe marketing.

“That’s not how it works,” I was told.

Have you ever seen something and thought, ‘That would have been cool to help design’?

“Not really.”

Is there anything that you don’t like designing?

“No.”

If it were up to you and you could pick the one thing to design that this company would be most known for being best at, what would it be?

“Again, that’s not really how it works.”

I got a good idea of how civil engineers think pretty quickly.

Lessons Learned

Marketing for a civil engineering firm is uniquely challenging. Civil engineering is essentially a commoditized industry. Contracted firms are usually chosen based exclusively on a lower bid or the promise of an earlier completion of the project and the designs and plan sets of one firm are often indistinguishable from the next. It all comes down to time and money. Small and medium-sized firms in particular tend to offer a large variety of services in addition to design work to keep a steady flow of billable work coming in, essentially doing whatever work for whoever will pay. Competition is high. Firms want to stick out, and at the same time may see what it takes to stick out as an interruption to their work.

Not surprisingly, the industry is conservative by nature. Marketing’s purpose is seen as “making things look shiny.” Business development strategies, collecting data and adopting metrics… not really something a little glitter can fix. This can make for short attention spans and lukewarm support for anything outside of making things look shiny. The main challenge then, was in selling the infrastructure that was needed to support both the ongoing business as well as the episodic pet projects that would periodically be thrown my way.

From day one I researched everything I could about the industry and engineers (yes, there’s plenty of data on the behavior of engineers). The more quickly I learned those, the faster I could get to work doing what I did best. The research was important for external marketing and gave me insight into how my colleagues operated. From there, it was just a matter of learning how they communicated. I picked that up along the way.

Here are the five most important lessons I learned:

1. Draw Everything (Make it Visual)

Sure, it’s always nice having some kind of visual accompaniment when talking about or explaining something abstruse. Even when the subject is straightforward it just feels nice on the eyes and brain to have a visual something to refer to. No doubt, a dive into the esoteric or expert-level anything often requires a visual aid. I have friends that are impressive in their ability to teach concepts of particle physics, but I can say without shame it’s unlikely I would have come to understand the principles of quantum electrodynamics had it not been for Feynman’s sketches.

While engineering is often associated with orderly systems, I would argue that no professional relies more heavily, or finds greater comfort and order from tables, certainty, and tolerances, than a civil engineer. They draw everything. Everything. From designing a gate over a water discharge duct to keep it from shooting into orbit, to an eight-hour bread-making regimen, nothing, it seems, can really be adequately explained, discussed, or communicated without a dry-erase marker in hand. I found the best way to get something across to my engineer colleagues was to do what they do- if it could be drawn, I drew it.

2. Model Empathy

Seriously, draw everything. It came as an epiphany well into a meeting with an engineer board member after several bewildering minutes of trying to explain to him why it was important for the company to care about how it was perceived- not only by its clients, but its future employees and possible future clients. Good marketing comes from a place of empathy. Sure, it’s obvious many marketers still don’t get that, that’s absolutely apparent. What I honestly couldn’t comprehend at the time was how someone with so much stake in a company could require convincing to care that others care.

Not everyone has an intuitive sense of empathy. Still, even an imaginative projection of a subjective state can be drawn in a way to explain what it is and subsequently, how it translates to long-term growth and positive ROI. Make the concept of what an actionable how. Models like the sales funnel only have real meaning once they can be explained why clients and customers become clients and customers. Draw what it means to care.

3. Use Their Language

Identifying the preferred mode of communication among teammates and stakeholders enables you to tailor messaging to be more easily understood and increase your chances for their buy-in- important when discussing non-engineering things to an engineer where boredom sets in quickly (like discussing the consideration of the perceptions of others for marketing). Not just drawing on the board for clarity, but adopting the vocabulary accompanying the language and the symbolism of how they express themselves through drawing.

For instance, using words like ‘footing’, ‘reinforce’, and ‘structured’ when communicating with a structural engineer, or ‘flow’ and ‘confluence’ when communicating with a drainage engineer. You get the idea. We know how others think as much by how they communicate as by what they communicate. Communicating with others in their own mode makes them more interested and receptive, and more importantly, it shows you care.

4. Find the Visionary Allies Early

When there’s a project to tackle some people shine in the execution phase, others in the planning phase. It makes sense that for something like a marketing project engineers prefer the latter. The planning phase is the designing phase, and engineers are designers. When it comes down to actually building a system like a marketing program interest wanes- more so when the system being designed relies on abstractions like ‘what the client wants.’ An engineer’s job is to define spec, not what’s above it.

There’s also the nature of the business, what actually brings in the revenue. When the final design for billable work is completed, other billable work is pursued. The entire business runs on this pursue-design-pursue model that permeates the culture of the business itself. When the planning is over everyone, it seems, wants to move on to the next project.

Non-engineering projects are taken on with as much energy and preparation as engineering projects- committees and exhaustive lists are frustratingly popular for this sort of thing. But when it’s time to execute and do the work the fanfare dies down and interest dries up. Hard-won resources are gradually reallocated without warning.

Visionary allies, those that can see the value of what the work means for the business and themselves, were hands down my single greatest resource for a successful project. More often than not for me, they were not the executives gunning for the project in the first place. Most weren’t even on the project teams. Rather, they were individuals who sought ownership in something transformative. They might have been in it for the fun, the skills, the opportunity to be included… whatever, they wanted to see it done and it satisfied something real.

Getting to know as many people as I could early on served me well when I needed my visionary allies. It’s not a common thing in engineering firms, being super sociable. Take advantage of it, it yields great returns.

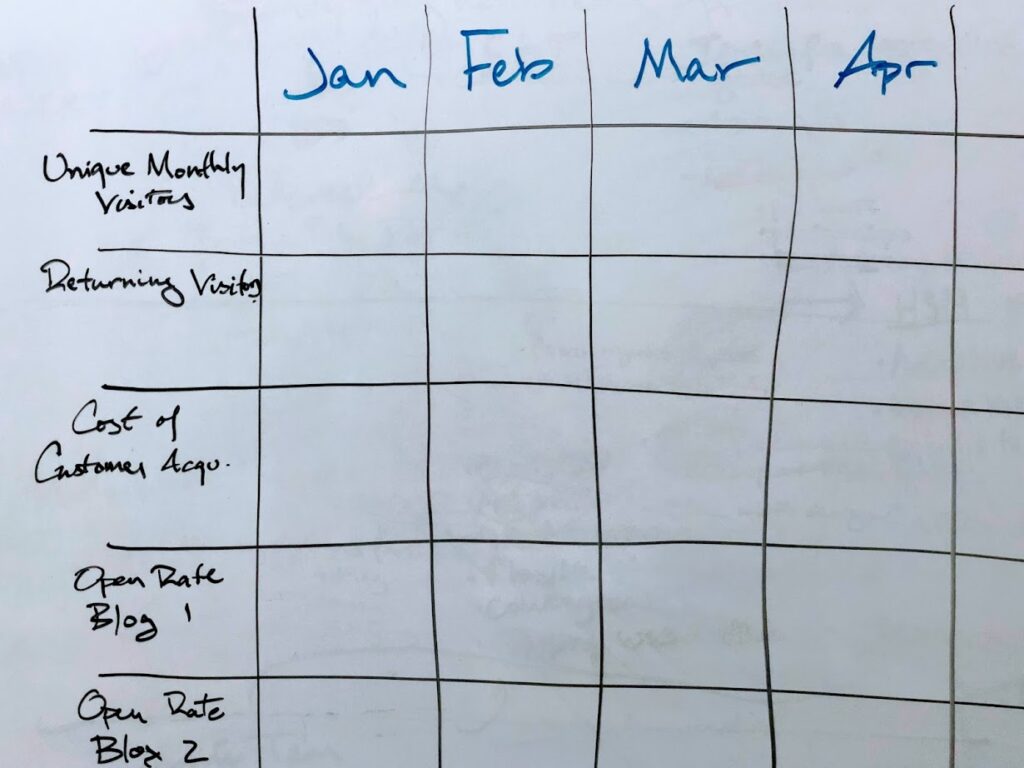

5. Make an Empty Metrics Table

Yes, risk tolerance is an individual thing, but seeing as how risk in the industry was described to me several times in the same terms, ranging from a project going over budget to people dying from a faulty design (with little else given in between), I feel pretty comfortable saying civil engineers have a low tolerance for risk. In a profession where pursuit of the perfect design relies on precise tables, known tolerances, and mathematical formulae, uncertainty is antithetical to their very nature. Simple ideas for solutions to seemingly innocuous problems could evoke discomfort or anxiety. This complicates things somewhat when discussing things like positioning, tactics, and strategy for the business that rely on assumptions themselves- not to mention testing the assumptions.

Tip: Avoid the word ‘experiment’ entirely. If you must, use ‘test’, it’s got a less ‘iffy’ connotation.

To test any assumptions, we need data. To measure the data, metrics. The firm I worked for had neither. Nothing was tracked. Successes, failures… they didn’t know what worked for them and what didn’t. I really was creating a marketing program from scratch, and for the board the idea of collecting data was fraught with risk.

Enter the empty metrics table.

The purpose of the empty metrics table is to change focus from the process of collecting data to the desired result of acting on it- the certainty to make decisions with confidence for long-term growth of the company. It’s empty for three reasons (besides the fact that there’s no data to measure yet):

1. It introduces possibility, and possibility is optimistic.

2. While numbers will be recorded onto it later, the blank cells that are there now are free of interpretation. They’re in a binary ‘0 state’. Any number added effectively makes a cell non-zero. The simple presentation in essentially binary terms makes the idea of the process of gathering data and acting on it less daunting. Binary is good.

3. In simple terms it shows what your focus is, what you’re doing with your time, and why your work is valuable.

2. While numbers will be recorded onto it later, the blank cells that are there now are free of interpretation. They’re in a binary ‘0 state’. Any number added effectively makes a cell non-zero. The simple presentation in essentially binary terms makes the idea of the process of gathering data and acting on it less daunting. Binary is good.

3. In simple terms it shows what your focus is, what you’re doing with your time, and why your work is valuable.

Conclusion

I took a sales mindset in everything I presented to the company’s board. How I communicated was as important as the things I advocated. I can’t promise that these lessons will make marketing for engineers easy, but they might mitigate resistance and increase the likelihood of understanding and adoption of your ideas.

Sometimes there’s immense value in just quietly watching and listening.