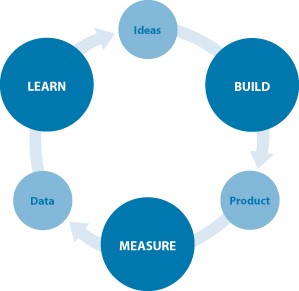

For a product, it’s the simplest and barest you can get away with- buggy and low-quality, only the essentials, and probably not the one you envisioned. Early on you don’t know what quality is anyway, you don’t even know who the customer is. It serves its purpose- a working model to put in the hands of innovators and early adopters, to test as fast as possible, and to serve as a model for future iterations based on customer feedback. This minimum viable product (MVP) is your first experiment. It will teach you what the customers want, and what is a waste of time and resources. If any feature, process, or effort does not contribute to your learning, remove it.